Let's Play Blackjack

• 17 min read

I've always been interested in the game of Blackjack and understanding how "optimal" certain moves are. I wondered if I could apply machine learning to Blackjack in order to understand the game more deeply. Let's dive deeper...

The game of Blackjack

Blackjack is a game played against the house. The objective is to get a higher card total than the house, without going over 21. At a given point in time, depending on the cards at play, a player can hit, stay, double, split, surrender. For the purpose of this analysis, I don't care about insurance or any other side bets. In blackjack, possible actions are conditional on the state that you are in, and the number of moves you have already taken. For example, after electing to hit, you can no longer double, surrender, or split, so the action space changes. If you don't have a pair, you can't split, etc...

After the players are finished with their round, the house draws cards until they have at least 17. Once the house is finished, rewards are distributed accordingly. A caveat is that if the house has natural blackjack, then the players cannot move and they lose immediately, unless the player also has natural blackjack, then they push. If the player has natural blackjack, and the house doesn't, they win immediately with a larger payout.

Here's how results are determined:

- player 21 : player loses

- 21 player house : player wins

- 21 player house : push

- player house 21 : player loses

- player surrenders : player forfeits half their wager

Depending on which environment you play in, the rules might differ a bit. I'll outline common rules that I elected to use for my analysis, although these can be adjusted easily:

| Rule | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Dealer hits soft 17 | false | |

| Push on Dealer 22 | false | some low minimum tables have this... |

| Double After Split | true | |

| Hit After Splitting Aces | false | |

| Blackjack Payout | 3 / 2 | |

| Allow Surrender | true | |

| Split any Ten | true | whether you can split any cards with a value of 10 |

I use 6 decks, and cards are not replaced until a "stop card" is reached, which is 66.67% of the way through the deck.

Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement learning is an application of machine learning where we're specifically tasked with maximizing some cumulative reward from a series of states and actions taken.

The goal of an RL agent is to maximize its cummulative expected reward

Think of trying to create an agent that moves through a maze. We don't have “ground truth” or direct “labels” about what the immediate action should be. However, we know that if the agent completes the maze efficiently without human interference, then it was properly trained. Maybe each step receives a reward of -1, and reaching the goal receives a reward of 10. Surely, reaching the goal in the least number of steps leads to the highest cumulative reward. How do we train this? Well, that's where Reinforcement Learning comes in.

In the game of blackjack, we have an environment. Let's think of this as the rules of the game, the objective, and generally just the boundaries of what's possible in the game. At each point during the game, we observe a state. Simply put, this includes a player's current cards and the face-up house card (let's assume we have no idea what the card count is, as we easily forget what cards we've seen previously). We are presented with a policy of possible actions to take. What is our optimal action according to this policy? Can we learn what the optimal action should be? We simply care about maximizing our expected total reward from the series of actions taken.

Model-Free vs Model-Based

There are 2 approaches that we can take for reinforcement learning. One is model-based learning, where we explicitly learn a model of the environment. We'd learn transition probabilities, which is the probability of taking an action, and rewards. In model-free learning, we don't explicitly learn a model of the environment, and instead, the model directly interacts with the environment and learns through trial and error.

There are tradeoffs to each method. Model-based approaches can be more efficient. Model-free approaches can be more generalizable and easier to implement. While the dynamics of Blackjack are quite simple, there are stochastic elements via the shoe and random cards that can be drawn at a given time. For this blackjack approach, I elect to use model-free reinforcement learning via Q learning.

Exploration vs. Exploitation

Exploration vs. Exploitation is a core problem of reinforcement learning. How much new exploration do we do of the space, versus how much do exploit the current knowledge of what we know is “good” or “bad”. Each have their tradeoffs, to some extent. If we always exploit our current knowledge, we'll never find potentially better alternative actions. If we always explore, we'll never take advantage of the learned knowledge of good actions. There are ways around this during the training process, such as:

- Greedy policies

- We always take the action that we know is best given our current information.

- Prevents exploration.

- -Greedy policies

- Each episode, with probability , we randomly take an action, otherwise we take the best action.

- Through learning, we can decay the epsilon value, such that we transition from high exploration initially, to more exploitation later in learning.

- Posterior Sampling:

- Each episode, we sample from the Q-space to determine an action.

- State-action Q values that are “good” are more likely to be selected, but we never allow for zero probability of selecting a “less good” action given the policy and the current state.

In this analysis, I use an -Greedy action selection policy, which I decay over time such that we initially mostly explore, and over time we exploit better actions.

Q values

Blackjack is an episodic task; observe a state, take an action, receive a reward, and repeat until the gameplay ends, meaning we've reached a terminal state. In blackjack, we don't observe rewards for every action, we only observe these rewards upon a terminal step that completes a round. In a markov decision process, Q Learning finds an optimal policy that maximizes the expected value of the total reward over all states visited in a sequence. Q values can be thought of as measures of actions in a given state.

Traditionally in Reinforcement Learning, we can observe the Value of being in a given state. Ideally, we'd want to take an action that leads to the maximum value of the next state. Newer approaches abstract this further, and introduce the concept of Q values, which denote a measure of state-action pairs. Rather than simply observing Value of a state, we observe a Q value of a state-action pair, and can make our selection action accordingly.

Through reinforcement learning, we aim to learn to the Q function through iterative approaches. I'll get into this more later.

The “states” I use are: Player Card Total, House Card Shown, Useable Ace. The “actions” are: Hit, Stay, Double, Split, Surrender. Each pair of these will have an associated Q-value. As mentioned earlier, not every action is feasible given the current state, so these unreachable states are “masked” given the valid moves determined by the Player module.

Q[(10, 4, false)] = {

"hit": 0,

"stay": 0,

"double": 0,

"split": 0,

"surrender": 0,

}On-Policy vs. Off-Policy

There are 2 different types of model-free reinforcement learning algorithms that I could use: on-policy and off-policy learning. On-policy uses the same strategy for both the behavior and target policies, it learns the Q values for the policy it's currently following. Off-policy learns the Q values for the optimal policy, which might be different than the one it uses during exploration. This doesn't seem like too big of a difference at first, but hopefully I can explain this a bit more.

Iteratively learning Q values in this model-free environment requires interacting with the environment. From a state, you take an action, observe a reward, and learn accordingly. I'll define the following:

= current state

= next state

= current action

= next action

= next action (greedy)

= q value

= learning rate

= discount factor. How important future actions are (0, 1)

In either method, at each state , we take an action , receive an immediate reward , and end up in state . In either case, we now need to update our Q value for that state-action pair .

An implementation of on-policy learning is through the SARSA algorithm (State-Action-Reward-State-Action). Updates to each Q value takes form below.

Think of this update step as trying to fit to a target value of . We have , the "greedy" action, which follows the same policy as the one used to determine . By this, I mean, if we follow an -Greedy policy (probability of selecting a random action) to determine our action , then we'll use that same policy to determine the next action to take so that we can update our Q value. Whatever is, will guide us to our next state .

for _ in range(n_episodes):

action = select_action(state)

done = False

while not done:

next_state, reward, done = step(action)

next_action = select_action(next_state)

q_target = q[(next_state, next_action)]

update_q_value(state, action, reward, q_target)

state, action = next_state, next_actionAn implementation of off-policy learning is Q Learning, where updates are taken as such:

It's a minor difference, but follows an off-policy approach, where we try to fit to a target of . Whatever state we fall into after taking action following our -Greedy policy, our target is simply the maximum available Q value to us in that new state . This state doesn't become our actual next state, like they do in SARSA, we still need to select an action according to our -Greedy policy.

for _ in range(n_episodes):

done = False

while not done:

action = select_action(state)

next_state, reward, done = step(action)

if done:

q_target = 0

else:

next_action = get_best_action(next_state)

q_target = max(q[(next_state, next_action)])

update_q_value(state, action, reward, q_target)For this analysis, I elect to use Q Learning.

Q learning

Just to reiterate above, we have the following to define our update to the Q values:

= current state

= next state

= current action

= next action

= q value

= learning rate

= discount factor. How important future actions are (0, 1)

At each state , we take an action , receive an immediate reward , and end up in state . Assuming that is not a terminal state, we can evaluate in this new state as well (if it is terminal, we'll assume it's ). For terminal steps, will be the observed reward from gameplay, for non-terminal steps, the reward will be zero. Essentially, we are taking a weighted average of the current value and new information, where R + \gamma * max_a(Q(s',a')) is the target value we are trying to obtain. We'll initialize all Q values to .

This requires storing the Q values of all state-action pairs in memory. In our case of Blackjack, without accounting for card count, this is a tractable problem computationally, which is why Q learning is a valid approach.

My Approach

I created some extensible python modules to be able to play this game. It consists of 3 main modules, which are the Cards , Player , Game modules. I won't go into the detail of these, but we're able to efficiently dictate gameplay for 1 to many players.

Next, I wrote some helper functions to enable training and inference. Some of these include functions to generate episodes, select best actions, learn a policy, and accumulate rewards from games and rounds per game.

I assume that only 1 Player is used during training, who wagers 1 unit each round. I haven't evaluated the training procedure for more than 1 player at a time, but since each player independently plays against the house, I can't imagine there is much difference.

I train for rounds, use , decayed , -Greedy action selection, where is decayed. I evaluate every rounds, where I assess games of rounds each, and accumulate average rewards.

To dictate the decay factor, I use the following:

def get_decay_factor(max_val, min_val, n):

return np.log(max_val / min_val) / n

def get_current_decay_value(max_val, decay_factor, n):

return max_val * np.exp(-decay_factor * n)

eps_decay = get_decay_factor(1, 0.1, n_episodes)

lr_decay = get_decay_factor(0.1, 0.001, n_episodes)

for i in range(n_episodes):

lr = get_current_decay_value(0.1, lr_decay, i)

eps = get_current_decay_value(1, eps_decay, i)Q values are updated after each timestep, not after each episode. We're able to achieve more efficient training this way, and also reduces the time complexity a bit.

Action Masking

In order to properly sample from the Q space and determine the optimal policy, each player's turn has the action space masked according to their current state. For example, “double” is only available as a first move of a hand. This means that after the player's first move for a hand, “double” is masked in the action space and will never be sampled from or be selected as an optimal play. Doing this, versus adding additional partitions to the state-action pairs, allows me to share more information across iterations.

For example, I've seen implementations where the state-action pair includes player_total, house_shows, useable_ace, can_split. Actually, this was my first implementation as well. But abstracting away can_split, and using action masking instead, led to more efficient training and more shared information between states.

Consider infrequent states, such as having a pair. We'll use a pair of 7's, for example. If we used can_split as a state, we'd have . We'd have very little knowledge about the other actions, as this state is so so infrequently visited. By abstracting away can_split, and using action masking, when a pair of 7's is observed, we can borrow information about hit, stay, double, surrender for all card combinations that give us .

Training

We can simulate gameplay and learn an optimal policy in each iteration. So, Q values are updated every timestep, but the learned policy is only evaluated every iterations, to speed up training.

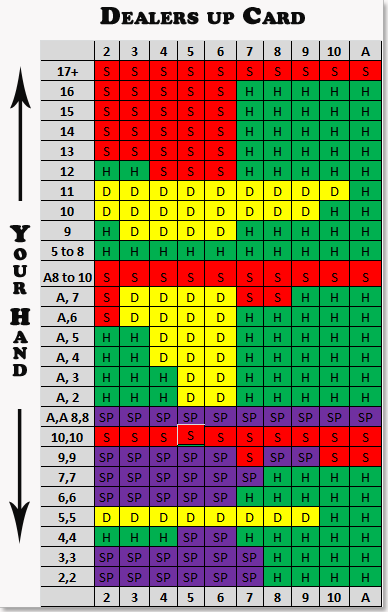

During each evaluation period, we can aggregate average rewards, but also percent of correct moves compared to a baseline "optimal strategy" that I found online. I partition these percent correctness scores by Hard Total, Soft Totals, Splits, so I can truly quantify where the model is performing worst. There are many intricacies that I'm leaving out, but they can all be found in the code in my github.

Some states are visited very infrequently. Empirically I found that Q values didn't converge for these. What I ended up doing is finding a aggregate of cards that were visited infrequently (basically just pairs and soft totals), and I force the Player hand to be initialized with these cards every 10 iterations. This at least seems to help with soft + split partitions approach the baseline performance more feasibly.

Evaluation

Now that the model is trained, I can evaluate its performance and its value function.

Performance

Below I compare policies and their reward distributions. To do this, I play games of rounds of blackjack, for each policy. For each of these games, I can find the average reward per hand per round, and plot the distribution of these.

| Policy | Description |

|---|---|

| Learned | the learned policy from training |

| Accepted | baseline optimal policy found online |

| Random | completely random policy |

| Mimic House | stay on anything higher than 16, hit otherwise |

While we have a rewards distribution, we can can capture the expected value of reward per round, in terms of units, for each policy.

- Learned: -0.0082

- Accepted: -0.0094

- Random: -0.4243

- Mimic House: -0.0628

Value Function

Next, I can determine the value function to be able to visualize our state values.

tells us, according to a policy , what the "value" is of being in state . We can relate this back to , as I'll show below. First, we have the equations for and . We are trying to maximize the expected cummulative discounted reward according to our policy.

We can relate and by taking marginal expections over

Where is the probability of taking action in state . In our case, will equal 1 if the action is equal to , and otherwise, since we don't have transition probabilities and assume we always take the optimal action during inference, which leads to the following:

Performing this for all state-action pairs, partitioned by Hard Total, Soft Total, Can Split results in the following:

It's quite neat seeing these value functions arise. I think for the most part they're rather intuitive. We exclude player values of 21 from the analysis, as the action-space is empty.

Additional Analyses

There are so many additional analyses that can be done having created the Blackjack gameplay modules, outlined the blackjack environment, and trained the RL agent.

A lot of additional analyses is conducted in the notebook on github, but here I want to highlight the impact of bankroll, which I think is a really interesting component to dive into. A trained model isn't necessarily required to conduct these, but I'll use mine to get results empirically.

Let's assume you wager 1 unit every round, as that is the table minimum. Let's evaluate the impact of your total bankroll, using the same exact policy to play the game of blackjack.

Lastly, I found it quite interesting to assess how your expected value changes according to your starting bankroll.

It's a classic example of bankroll across various games. No matter what policy you follow, or how adept of a player you are, if you have a smaller bankroll, you are at a disadvantage. At least following a more optimal policy will help mitigate that risk, but only so much. Simply by chance, you might lose enough consecutive hands that would cause you be out of money. This is why we see drastic drops in EV compared to different bankrolls of players, despite following the same exact policy.

Conclusion

In this post, I walked through an overview of blackjack gameplay, reinforcement learning, and the model-free, off-policy Q learning algorithm followed by some additional analyses. While we're only using player total, house total, and useable ace as our state, we can extend this. Next, I'll dive into adapting this approach to Deep Neural Networks...